Deep Sea Mining: Business Payday or Crime Against Nature?

February 10, 2022 - Ellie Gabel

Revolutionized is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more here.

Deep sea mining, also called seabed mining or marine mining, is a relatively new field within the larger mineral extraction industry. The practice involves retrieving various minerals, metals, and other deposits – like tin, diamonds, and sand – from beneath the surface of the ocean floor. Deep sea mining typically occurs at ocean depths of at least 200 meters (656 feet) and up to 3,700 meters (12,139 feet). It uses powered bucket systems or hydraulic pumps to move materials.

Despite its name, most deep sea marine mining occurs in relatively shallow coastal areas, That’s where the materials in question are most prevalent.

Marine mining offers considerable potential, but scientists also urge caution. What is deep sea mining? How is it carried out and what are the risks and benefits of seabed mining?

What Is the Purpose of Deep Sea Mining?

The concept of deep sea mining originates with ecologist Hjalmar Thiel’s explorations of the remote Pacific Ocean in the early 1970s. Thiel ventured into these waters to study meiofauna, which are small organisms living with metallic nodules deep in the ocean. Accompanying him was a cadre of motivated mining experts, who were eager to exploit what is still believed to be one of Earth’s largest undisturbed caches of ores and minerals.

Thiel urged his companions to exercise caution, saying any attempt to mine such a region – including disposing of the resulting waste sediment into the ocean – could have a catastrophic effect on the rich tapestry of marine life, from vertebrates down to the smallest microbes. It took decades for other groups to perform similar research, all of which points to a robust conclusion. It was that engaging in industrial-scale deep sea mining could provoke more ecological damage than the benefits justify.

Today, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) grants exploratory permits to mining ventures interested in deep sea mineral extraction, but there is very little practical commercial deep sea mining going on at present. That could change quickly, however.

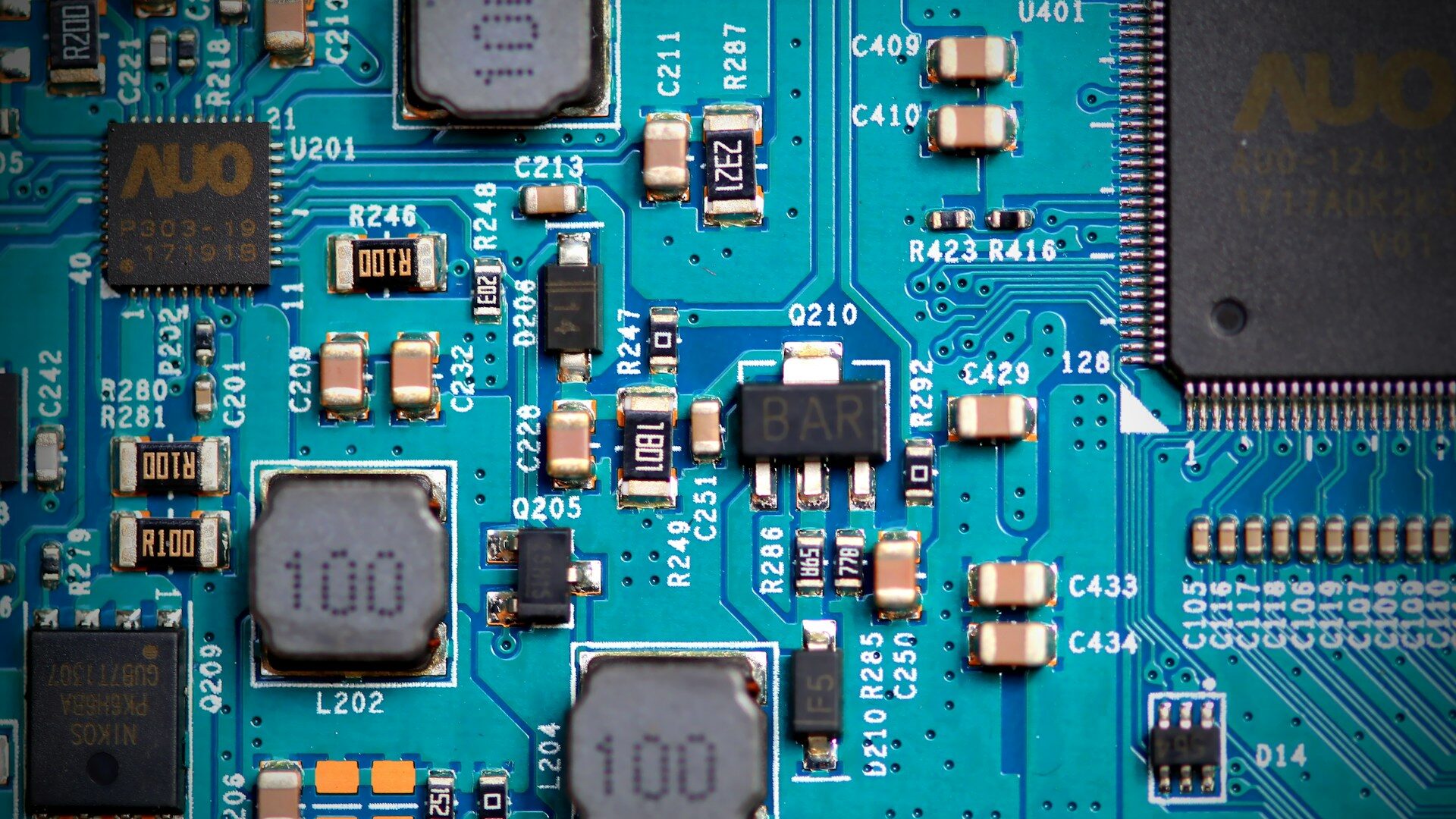

In 2022, the primary motivation for exploring deep seabed mining involves the looming scarcity of certain metals on Earth’s surface. They’re necessary for fabricating high-tech devices, such as solar cells, LCD screens and batteries. Consider the outcomes if scientists and engineers design a safe seabed mining process. It could go a long way toward curbing shortages of critical electronics components. Some substrate materials involved in CPU and GPU manufacturing, for example, saw up to 20% price increases in just a single year.

People must develop alternative technologies or find reliable caches of rare earth metals to mine safely. Otherwise, the already-embattled automotive, aerospace, and commercial and consumer tech industries face further troubles. Other mining operations could positively impact the food and beverage supply chain. It needs artificial fertilizers derived from mined phosphorus.

How Has Deep Seabed Mining Proceeded So Far?

The rising prices of precious metals have driven corporations in many countries, including the U.S., China, Japan, India and Korea, to further their explorations of hydrothermal vents as potential mining zones. Japan brought online the first commercial-scale seabed mining operation situated at a hydrothermal vent in September, 2017.

Later years saw other ventures enter this burgeoning industry as well, though, with substantially varied results. For instance, the Solwara 1 Project in Papua New Guinea, by Nautilus Materials, would have mined, at scale, high-grade copper and gold resources from an intermittently active hydrothermal vent. After stalling several times during debates with the government, the 1,600-meter-deep venture was finally abandoned in 2019. The backlash from the environmental community was too intense to overcome. Additionally, protracted delays on the project eventually caused its backers to cut their losses and pull their funding.

Contractual Agreements Could Accelerate Seabed Mining

As of 2022, the International Seabed Authority has ongoing contracts with 19 governments and private corporations to explore and potentially mine the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ). It occupies some 4.5 million square kilometers of seabed between Mexico and Hawaii. The potential payload in this area includes deposits of many minerals instrumental in building modern infrastructure and technologies. They include manganese, cobalt, zinc, copper, magnesium, nickel and others.

How Does Deep Sea Mining Happen?

There are three main types of deep sea mining:

- Polymetallic nodule mining

- Polymetallic sulphide mining

- Ferromanganese cobalt mining

Each of these requires a variety of high-tech equipment. Remote-operated vehicles (ROVs) collect samples from potential sites using cutting and drilling tools. If the site looks promising, a mining vessel goes there begin operations.

Most seabed mining operations deploy either continuous-line bucket systems (CLBs) or suction systems powered by hydraulics. Current operations generally use the CLB system due to its relatively straightforward mechanism. It functions similarly to a conveyor belt and runs from the seabed to the ship.

Is Seabed Mining Profitable?

Deep sea mining could be hugely profitable if scientists and engineers can assuage fears about environmental degradation. Estimates suggest the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone contains more commercially viable mineral and metal deposits than all surface-level deposits on the Earth combined.

Enthusiastic market research from the mining sector shows investors expect rapid and impressive returns. They estimate its worth to reach $15.3 billion by 2030.

For companies interested in helping transition to clean energies and access other climate solutions, seabed mining could have hugely profitable and transformative potential. But what’s the real cost of seabed mining?

Is Deep-Sea Mining Dangerous?

Any type of mining operation carries significant human and environmental questions. Deep sea mining is certainly no different. Since seabed mining is so new, researchers still need to study the long-term impacts.

Scientists have reason to worry, though. The scientific community has been and remains concerned that disturbing or removing portions of the seabed will have a range of deleterious effects on the local ecosystem. They include:

- Increased toxicity of the water column

- Severely compromising oceanic biodiversity

- Destruction of habitats containing keystone benthic organisms

- Toxic leakage from equipment introducing harm to the environment

- Near-bottom and surface plumes of disturbed sediment could suffocate a variety of marine lifeforms over time

- Abyssal fauna located near hydrothermal vents are already vulnerable to disruptions; deep sea mining could drive many species to extinction

- Potential collapse of the food web as sun-dependent organisms starve from a lack of light, with cascade failures to follow

Local disturbances and artificial waste-sediment plumes will probably spread, too. Researchers anticipate any scaled-up versions of invasive deep sea mining techniques could cause the disturbed sediment that effect.

Opposition to Seabed Mining

Experts believe that seabed mining could destroy marine ecosystems humans haven’t even studied yet – along with the scientific lessons we could have learned there.

David Attenborough, perhaps the world’s preeminent natural historian, has called for a ban on deep sea mining. He calls the practice “devastating.” Ecology-focused nonprofit organizations, including the World Wide Fund for Nature and Fauna and Flora International, echo that sentiment. Even profitable corporations voice their opposition to the practice. That remains so despite many getting potential benefits expanded active mining zones. These companies include Samsung, BMW, Google, Volvoand others.

What Does the Future Hold?

At the end of 2021, a unanimous vote at the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) approved a global moratorium on deep sea mining. It happened after a long lobbying campaign by concerned scientists and conservationists.

Still, even with this vote on the books, the business-focused ISA remains under a two-year deadline to finalize licensing regulations for deep sea mining ventures. The IUCN vote represents a significant achievement. However, the movement to protect the ocean still faces considerable opposition. Said Jessica Battle, a senior policy expert at the World Wide Fund for Nature:

“The pro-deep seabed mining lobby is … selling a story that companies need [this] … to produce electric cars, batteries, and other items that reduce carbon emissions. Deep seabed mining is an avoidable environmental disaster. We can decarbonize through innovation, redesigning, reducing, reusing, and recycling.”

The degree to which the IUCN will influence the more corporation-friendly ISA remains to be seen. In the meantime, seabed mining remains a concept with as much potential for harm as for good – until and unless safer and less invasive technologies are developed to carry it out.

Revolutionized is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more here.

Author

Ellie Gabel

Ellie Gabel is a science writer specializing in astronomy and environmental science and is the Associate Editor of Revolutionized. Ellie's love of science stems from reading Richard Dawkins books and her favorite science magazines as a child, where she fell in love with the experiments included in each edition.