Does the TRAPPIST-1 System Have Too Much Water to Support Life?

April 26, 2018 - Emily Newton

Revolutionized is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more here.

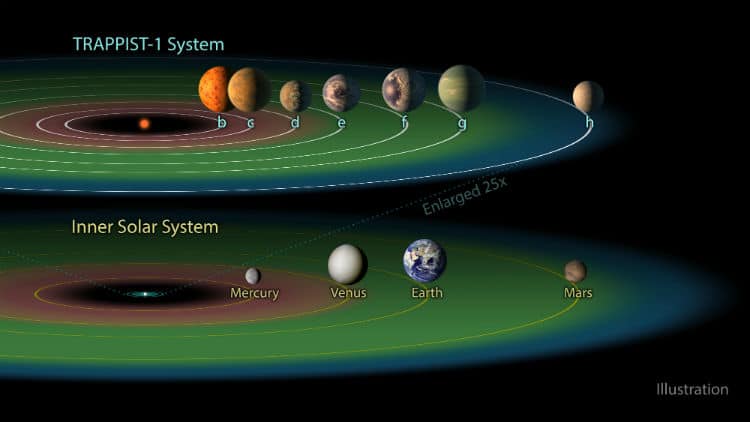

One of the main things we look for on the exoplanets we discover throughout the galaxy is water — water is one of the most important factors regarding a planet’s ability to support life. Not necessarily human life, but any life at all. One of the most exciting exoplanet discoveries in recent years is the TRAPPIST-1 System — anywhere from five to seven planets orbiting a sun, with at least a few of them in the star’s habitable zone. Is it possible for a system like this to be too good to be true? Could a planet have too much water to support life?

Water on Other Planets

If we look at planets that are, in this case, 40 light-years away, how can we tell how much water might reside on the surface of these remote planets?

A lot of it is speculation — the amount of water on the surface of these planets will depend largely on the amount of heat it receives from its sun. The star in the TRAPPIST-1 system is an ultra-cool red dwarf star, less than 10 percent smaller than our sun.

By studying the planets in the TRAPPIST system, and how they tug on one another, scientists have theorized how much water might be on those planets. Some of the seven planets in the system could contain more than 250 times more water than Earth’s oceans contains. The close orbits of the planets made it easier for scientists to determine the density of the planets. That density allows them to see how much water the planet’s surface might contain.

Of the seven planets, A and B are too close to the system’s star to support life. C, D and E are in the habitable zone and may contain liquid water, while F and G are probably too far away from the star to support liquid water — any water on their surface is likely frozen solid. Astronomy Magazine recently covered how astronomers were able to determine how much water was on some of the planets:

“By analyzing the host star’s chemical composition, along with the mass and radius of each planet, the software estimated that the two innermost planets (marked “b” and “c” on the image below) have less than 15 percent water by mass, while two of the outer planets (marked “f” and “g”) have over 50 percent water by mass.“

– Astronomy Magazine

Nonetheless, planets B and C still contain significantly more water than Earth. Water only contributes to 0.02 percent of our planet’s mass.

Lacking Hydrogen

While we have an abundance of hydrogen on our planet, in the form of water, there isn’t a lot of it in the atmosphere. Our atmosphere is primarily made up of nitrogen, oxygen and methane. Hydrogen tends to hold heat in a planet’s atmosphere, making it inhospitable to human life. In our own solar system, Neptune is a good example. The puffy, hydrogen-rich atmosphere of the 7th planet traps heat — it’s primarily more abundant on the gas giants found in the outer part of our solar system.

The three planets in TRAPPIST-1’s habitable zone appear to lack hydrogen — a good sign that these planets could potentially support life, however since they contain too much water, there isn’t the proper balance to kick start life on the planet.

Launching TESS

While TRAPPIST-1 might be one of the most exciting discoveries in recent years, with the launch of the TESS satellite, it may not be the only discovery we get excited about.

On April 18th, SpaceX launched TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. This satellite uses high-resolution cameras that will map the night sky, searching for new exoplanets in previously unobserved systems. During its two-year mission, TESS will observe more than 150,000 star systems, watching the stars to see if planets pass in front of them.

Scientists will process the raw data back on the ground. TESS will spend upwards of 27 days photographing each section of the sky. Most of the exoplanets we’ve discovered so far are still out of reach of potential human colonization. Even our closest interstellar neighbor, Proxima B, is four light-years away and would take more than 70,000 years to reach with our current technology levels. What this does provide is the idea that there are other planets out there that could potentially support life — human or otherwise — and when we finally have the capability to reach them, we may be in for a surprise

.Some plants, like Proxima B, may no longer support life due to their proximity to their sun, but the TRAPPIST-1 system could provide the template to show us what to look for when we try to find more exoplanets closer to home.

Revolutionized is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more here.

Author

Emily Newton

Emily Newton is a technology and industrial journalist and the Editor in Chief of Revolutionized. She manages the sites publishing schedule, SEO optimization and content strategy. Emily enjoys writing and researching articles about how technology is changing every industry. When she isn't working, Emily enjoys playing video games or curling up with a good book.