Revolutionized is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commision. Learn more here.

In 2016, an obituary went viral mourning the death of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. It informed readers that the reef, born in 25 million BC, had passed away, claiming that the existing structure of the reef had finally died due to climate change, El Nino and human intervention.

Nearly instantly, the viral image had scientists up in arms. While it’s true that some of the reefs have perished — a process called bleaching where the live animals in the coral die and leave behind their white skeletons — as of 2016, more than 3/4 of the structure was still thriving.

How are the rest of the world’s coral reefs holding up, and what changes can we make to try to save the reefs that are still surviving in our planet’s oceans?

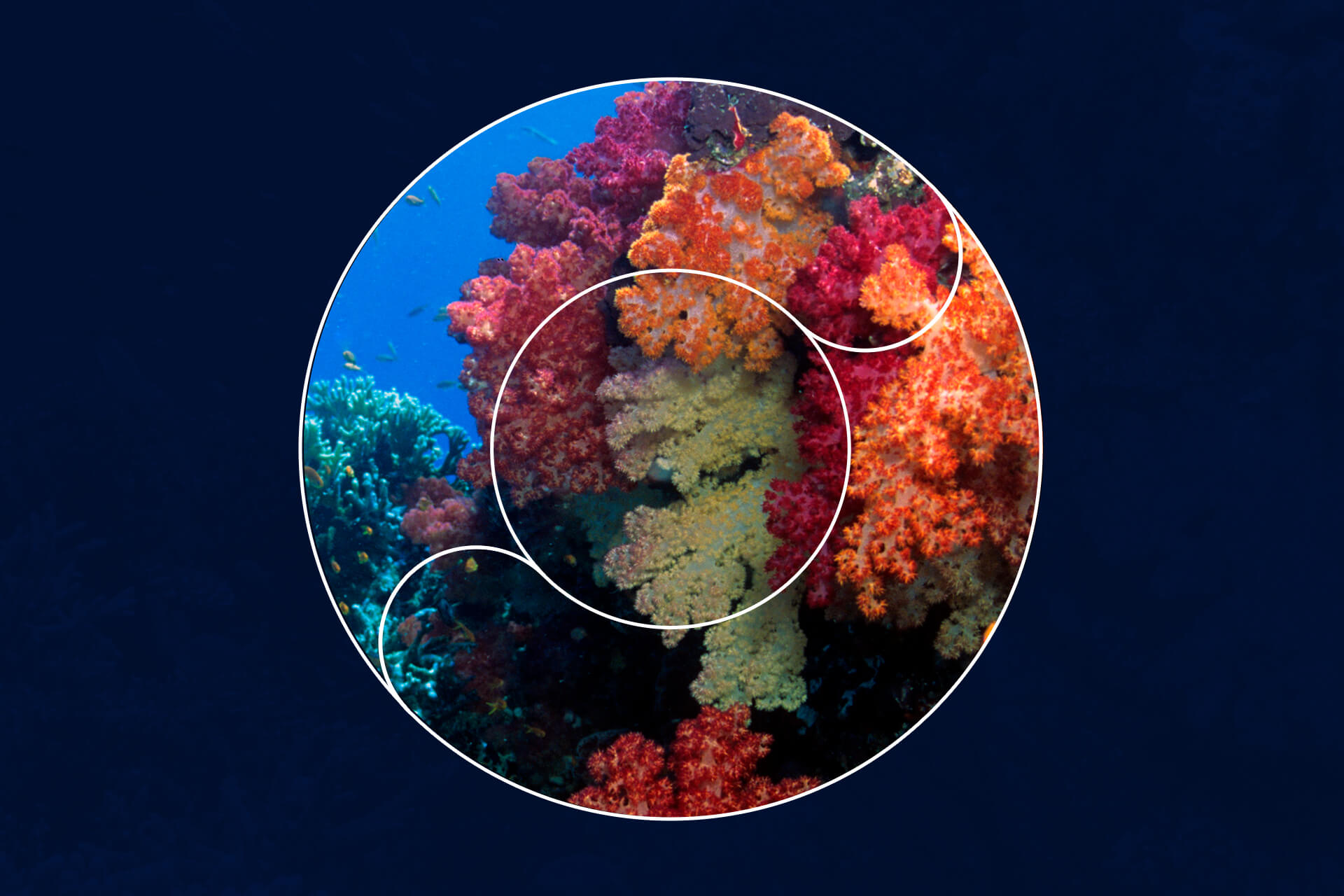

Though they look like massive stone constructs, coral reefs are living, growing animals. What does the life cycle of this fantastic creature look like?

As with most animals, the life cycle of a coral reef starts with the reproductive process. The coral polyps — the creatures that live within the calcium structure of the reef — release millions of eggs and sperm cells into the water. This act is called spawning. Once fertilization takes place, the eggs start to develop and eventually hatch into a planula larva.

These larvae may float on the surface for up to a month, collecting algae that help them to prepare for the next step in their life cycle. Some species of coral release an egg and sperm cell internally and hold the larva within the polyp until it’s mature enough to release.

Once the larva matures, it will settle down toward the bottom of the ocean in what will become its permanent home. If it lands on the seabed, a new coral colony will begin to grow. If it falls on an existing coral structure, it will add to that reef, changing and shaping it.

The larva then becomes a polyp and begins dividing itself in half. Each half is capable of doing the same, making identical copies that will spread and create a colony. Each polyp in the colony is an exact genetic duplicate of the original larva. At this point, those algae that the larva collected while it was floating on the ocean’s surface will go to work, producing calcium carbonate that makes up the hard surface of the reef. Once the polyp reaches sexual maturity, the process starts all over again.

We all know that stress is bad for us. In humans, it triggers the release of cortisol — the stress hormone — and adrenaline in our brains and can cause a variety of health problems. In coral, stress can be fatal. Coral reefs need a very particular climate to survive — water that has the correct PH level and is warm but not too hot.

If a reef gets stressed out, it ejects all of the algae that help create the calcium carbonate shell. This process is called bleaching because the algae also give the coral its iconic bright colors. All that’s left behind is the white calcium carbonate.

The Great Barrier Reef experienced two dramatic bleaching events in 1998 and 2002 that were attributed to El Nino, and two back-to-back bleaching episodes in 2016 and 2017.

These back-to-back events are worrying scientists because they didn’t give the reef enough time to heal between bleachings and could result in the death of the coral. Bleaching is a regular occurrence with coral, but it can take years or even decades for it to get back to normal. If coral gets bleached too often, it will lead to the coral reef dying.

Contrary to what that viral image suggested, the Great Barrier Reef and other structures like it aren’t dead — at least not yet. While it’s true that half of the Great Barrier Reef has died since 2016, the remaining coral is still surviving and even thriving.

This success may be due to a trait called ecological memory. When the coral reefs were dying in the 2016 bleaching event, they taught the polyps that remained how to avoid the same fate. The years 2016 and 2017 did hold back-to-back bleaching events, but instead of being as devastating as scientists predicted, less of the reef bleached in 2017. This fact is astonishing because the Australian summer was hotter that year than it had been the year before.

These reefs are still at risk. Ecological memory can only carry a reef so far, and with more than half of the structure dying within the last three years, we need to make changes to ensure that these vital parts of the ecosystem survive into the future.

We need to make changes to stop our remaining coral reefs from dying. We cannot continue as we have if we hope to preserve the coral reefs for future generations to enjoy. Global warming is increasing ocean temperatures around the globe, which is stressing the coral and leading to bleaching. It’s our responsibility to take the steps necessary to reverse or at least slow down climate change to ensure that these delicate ecosystems survive.

Revolutionized is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commision. Learn more here.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.