What Shapes the Interesting Way Our Neurons React to Placebos?

March 28, 2016 - Emily Newton

Revolutionized is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commision. Learn more here.

Expectation is a powerful force in the brain. Pavlov’s dogs, for example, were conditioned over time to expect food any time they heard the ringing of a bell. Their brains signaled their bodies to respond to the bell in the same way they would respond to food – with increased salivation.

Now, the power of expectation is being harnessed to reduce the amount of medication needed to treat Parkinson’s disease. Scientists have discovered they can train patients’ neurons to respond to placebos the same way they respond to the dopamine-stimulating drug apomorphine, which is used in the treatment of the disease.

How the Brain Works

Neurons are brain cells. They transmit information from electrical and chemical nerve impulses to other nerve cells, muscles or gland cells.

In other words, neurons allow a person to react to his or her environment by transporting stimuli. For example, when you touch a hot surface, your neurons send a signal of pain to the brain, which then responds by signaling the arm to move away from the source of the pain.

Parkinson’s disease is a neurological disease that affects movement. Those with the condition experience bodily tremors and stiff muscles. This is because Parkinson’s causes brain cells that produce dopamine naturally to die off. To alleviate their symptoms, patients take drugs such as apomorphine to activate dopamine receptors.

Teaching Old Neurons New Tricks

In research on the treatment of other types of disorders, people have been trained to respond to placebos, so scientists wondered if the same was possible for a neurological disorder such as Parkinson’s.

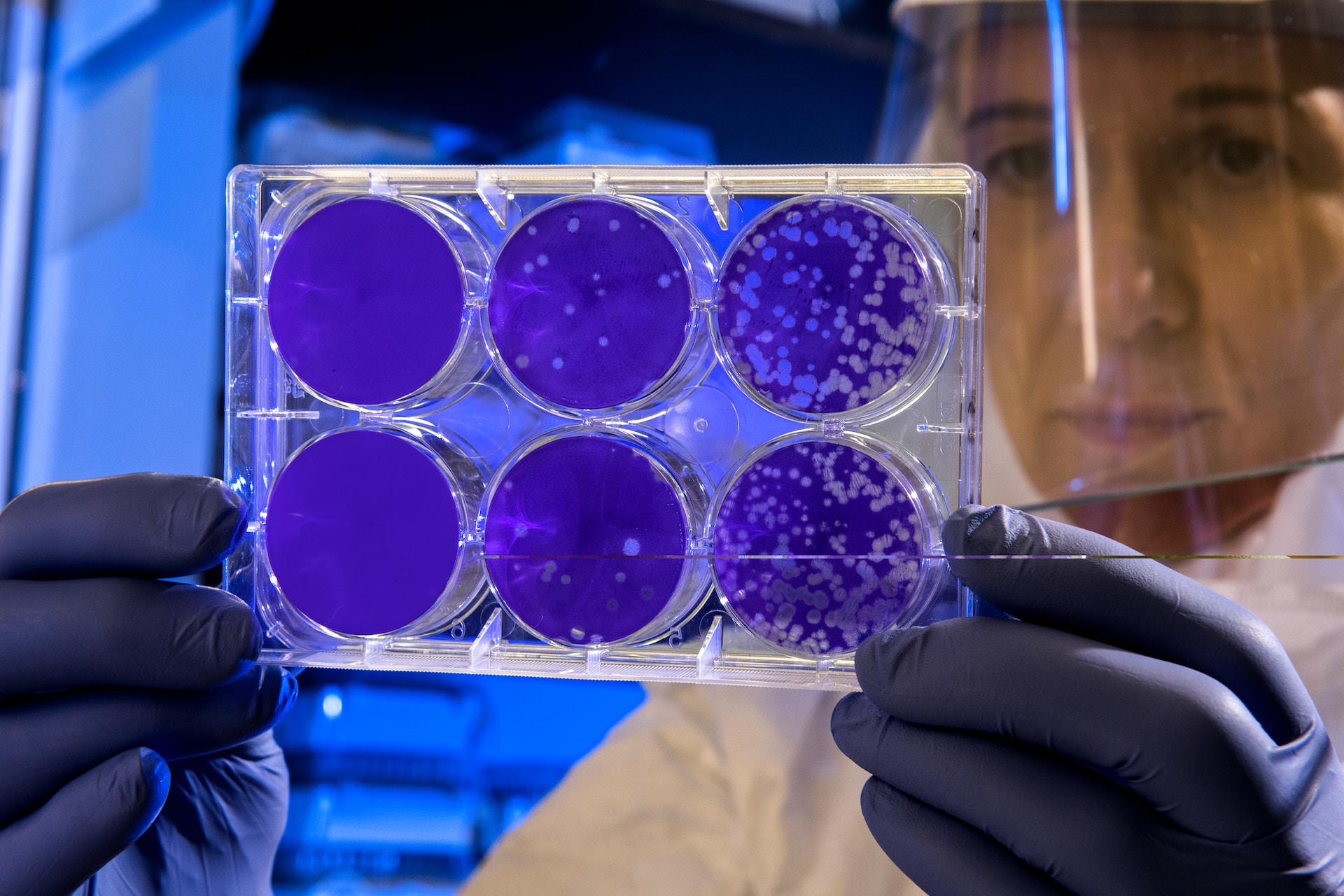

To test this, scientists studied advanced Parkinson’s patients who were to undergo a surgical treatment therapy called deep brain stimulation. The therapy involves the direct stimulation of the brain using electrodes, which deliver electrical impulses to improve movement capabilities. It is typically used for Parkinson’s patients whose symptoms can’t be controlled with medications alone.

Introducing Placebos

In the days before the surgery, patients received varying degrees of conditioning. Participants received between one and four injections of apomorphine every day.

Then, during the surgery, all participating patients were given an injection of a placebo consisting of saline solution and were told it was apomorphine. By measuring the activity of specific neurons being stimulated, researchers could measure the response to this placebo.

A neurologist assessed the patients without being told which treatment each one received. For those who had not been conditioned, the placebo produced no response.

However, it was determined those who were conditioned actually did respond to the placebo injection. Their neurological activity increased, and their muscles became less rigid.

The more daily apomorphine injections a patient received, the greater his or her neurological response to the placebo injection, meaning patients who received the maximum of four injections responded the same way to the placebo they did to the real drug.

Revolutionizing Treatment

The findings of this study have huge implications for future treatment of Parkinson’s disease and other disorders.

What’s great about a placebo treatment for Parkinson’s disease is because it involves no new drugs, improvements in treatment are possible without industrial production or clinical trials.

Additionally, by exploiting the ways in which neurons work and the expectations of the brain, the drug intake by patients can be reduced. Hopefully this means people would need to take less medication but still achieve the same clinical benefits of apomorphine.

here is one future challenge for medical researchers. The effect of the placebo response only lasts up to 24 hours. If the effect can be extended, even better treatment will be possible.

Revolutionized is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commision. Learn more here.

Author

Emily Newton

Emily Newton is a technology and industrial journalist and the Editor in Chief of Revolutionized. She manages the sites publishing schedule, SEO optimization and content strategy. Emily enjoys writing and researching articles about how technology is changing every industry. When she isn't working, Emily enjoys playing video games or curling up with a good book.